Evergreen has joined the mega-ship club with an order for 11 x 20,000 teu units. How many more carriers will follow?

The announcement last week that Evergreen has signed time-charter agreements with Shoei Kisen Kaisha, Ltd. for 11 Ultra Large Container Vessels (ULCVs) of 20,000 teu – the nominal capacity stated by builders Imbari rather than Evergreen’s operational estimate of 18,000 teu – means that the total sum for ships of 18,000 teu and above, either active or on order, has now passed the 1 million teu mark.

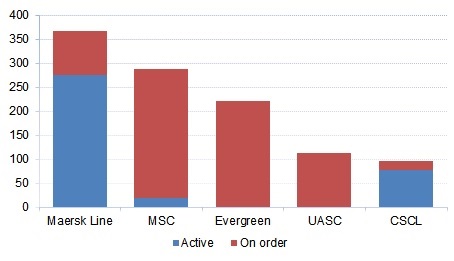

Figure 1

Containerships of 18,000 teu and above, Active and on Order, as of February 2015

Source: Drewry Maritime Research (www.drewry.co.uk)

Measuring about 400 metres in length and 59 metres wide these ships will join the CKYHE Alliance (Cosco, K Line, Yang Ming, Hanjin and Evergreen) services from 2018 through 2019.

Evergreen emphasised the main draw of these ships, the cost savings, with the ship’s new generation G-type main engine developed with a longer stroke in order to sail at lower speeds, helping to reduce fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions by an estimated 7 % compared with traditional main engines.

The 18,000 teu-plus club was formed by Maersk Line when it ordered the first tranche of 10 Triple E class ships in February 2011, which it followed in June of the same year with an order for 10 more.

Two years later, CSCL, MSC and UASC were suitably convinced of the competitive advantages of these leviathans that they ordered their own sets, and almost fully four years since the first Maersk order, Evergreen has become the fifth member of the club.

Evergreen’s reticence to jump in sooner is not without precedence. Amid the 2007-order frenzy for ships of 10,000 teu and above, demonstrating a remarkable predictive talent, Evergreen Group chairman and founder Chang Yung-fa memorably vetoed such a move saying that big ships would struggle with half loads when the global economy turns cold.

Chang Yun-fa, Evergreen Group founder and chairman, 2007

“Prepare for the bad times. I’m no soothsayer, but I have been in the industry for 40 years and have weathered a lot of storms. When the inevitable lull comes, the huge ships will suffer instability.”

Instead, Evergreen avoided the stampede and waited until 2010 to order 20 x 8,450 teu ships, followed by 15 more similar size ships the year after. It was only when the company moved away from its traditional independent status and forged closer ties with the CKYH carriers that it took the big-ship leap by ordering 10 x 13,800 teu ships in July 2012 (one year after Maersk’s Triple E order), which it backed up over the next two years with orders for 5 x 14,000 teu and 5 x 14,350 teu.

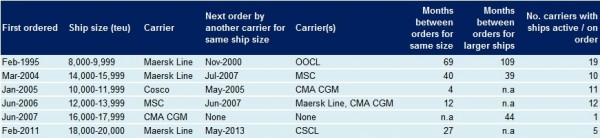

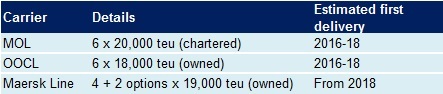

Table 1

Follow the Leader: Development of Big Ship Orders

Source: Drewry Maritime Research (www.drewry.co.uk)

Drewry has previously described the latest rush for ULVCs as an “arms race”, and outlined the supply pressure that they are adding to, see Slipping into the future. However, a more apt description is probably “Follow the leader”. If we take a step back into the recent past, the history of orders for the latest biggest ships reveals a common trend; Maersk Line makes the first order and other carriers eventually follow, see Table 1. The main change is that carriers are taking less time to play catch-up.

For example, Maersk had a five year start on its rivals when it ordered its first 8-9,000 teu ships in early 1995 – delivered from late 1997 – as the next comparable order only materialised in November 2000 with two 8,063 teu time-charter ships for OOCL that were delivered in mid-2003.

While other carriers slowly got their own 8-9,000 teu ships, Maersk raised the bar to new heights in March 2004 with its eight 15,550 teu Emma Maersk series, delivered from the second-half 2006. This time the response was quicker, at just over two years rather than five, as MSC ordered smaller but comparable versions of their own: 8 x 13,800 teu and 5 x 13,800 teu ordered in June 2006 and delivered early 2009.

It wasn’t until June 2007 that the Emma Maersk ships were surpassed in the orderbook, when CMA CGM opted for three 16,020 teu ships, delivered late-2012. There followed another period of catch-up, before Maersk made another quantum leap with an order for 20 x 18,220 teu Triple E ships, ordered in February and June 2011 and delivered from 2013 through 2015.

This time, it took CSCL just over two years to react with a May 2013 order for 5 x 19,100 teu ships, the first of which, CSCL Globe, was delivered in January 2015 to briefly become the world’s largest containership. CMA CGM also moved for slightly smaller 17,000 teu units in June 2013, while MSC (via time charter) and UASC ordered 18-19,000 teu ships in July and August 2013. Both carriers added more last year, leading us to the Evergreen / Shoei order.

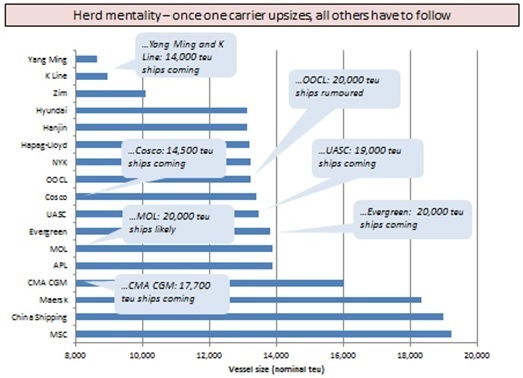

Figure 2

Largest Vessels Deployed on Asia to North Europe Trade, January 2015

Source: Drewry Maritime Research (www.drewry.co.uk)

Maersk Line has clearly enjoyed considerable first-mover benefits, demonstrated by its market leading profitability in recent years. Eventually, all other major carriers, to varying degrees, have picked up the baton and looked to replicate its success by introducing comparable vessels, see Figure 2.

However, as the historical analysis in Table 1 shows, as the size of the biggest ships get larger, the opportunity for carriers to enter that size club gets smaller. The market has grown sufficiently that all of the major carriers can now deploy ships of 8-10,000 teu, but the pool of carriers is shallower for ships of 12-14,000 teu with the number of operators at only 12.

In the short-to-medium term the demand simply does not exist for all lines to have 12 x 18-20,000 teu ships required for a weekly service of their own. What this means is that the container industry will effectively become a two-tier arena with the haves enjoying far greater economies of scale over the have-nots.

The new mega-alliances will offer the have-nots access to the big ships through vessel sharing agreements. Drewry expects future ULCV orders to be placed according to alliance needs rather than meeting individual lines’ requirements. Although they are yet to be confirmed, the highly anticipated orders by G6 Alliance carriers OOCL and MOL for two sets of 6 x 18-20,000 teu ships would be a clear example of this way of thinking.

This approach will spread the benefits across the alliance members – assuming the costs are equally shared – and at the same time will prevent the industry being flooded with far too much capacity.

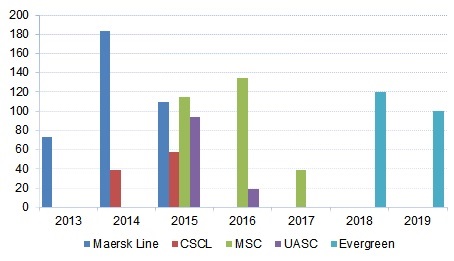

Figure 3

Estimated Delivery Schedule for Containerships of 18,000 teu and above, by year and ‘000 teu

Source: Drewry Maritime Research (www.drewry.co.uk)

Table 2

Rumoured 18,000+ teu Orders in the Pipeline

Source: Drewry Maritime Research (www.drewry.co.uk)

The expected orders from MOL and OOCL will enable the G6 Alliance to join the big ship club, but they will merely limit the damage to alliance’s market share in the East-West trades as other carrier groups have bigger plans in place. Despite this fact, at present it seems unlikely that more orders from other G6 members will materialise in the near term.

The 2M carriers, Maersk and MSC, have a distinct advantage in terms of 18-20,000 teu ships already on the water with another 360,000 teu worth to be delivered. Having made the first move, Maersk has no such ships due beyond 2015 and is expected to want to extend its advantage with another order soon. There are also whispers that MSC might be after more too.

The Ocean Three lines – CMA CGM, CSCL and UASC – are well catered for up to 2016 with the latter two carriers taking delivery of around 132,000 teu worth of 18-20,000 teu ships. CMA CGM has a number of ships just outside this range at 17,700 teu, all of which are due 2015, and so could well be tempted to make the step up.

The Evergreen order represents the only 18-20,000 teu ships for the CKYHE Alliance, for which they will have to wait at least three years. The next biggest orders are 30 x 14,000 teu units for Cosco, Evergreen and Yang Ming, which suggests they have made their bed and won’t have the room for more of the larger ships.

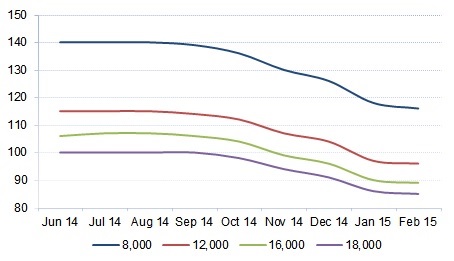

Figure 4

Estimated Cost per RV Slot, Asia to North Europe Trade (100=18,000 teu, 1 June 2014)

Source: Drewry Maritime Research (www.drewry.co.uk)

The fear for lines that do not make the leap to the big ships is that they will get left behind in terms of cost competiveness, but they can at least take some solace that lower fuel prices are reducing the scale advantage of ULCVs.

Figure 4 demonstrates the estimated unit cost differential between ship sizes in the Asia-North Europe trade, driven by the prevailing bunker costs at Singapore at the start of each month. The data reveals that when bunkers were at their peak in June 2014 the cost difference between an 8,000 teu ship and an 18,000 teu unit was 40 points, but as fuel costs came down the gap has narrowed to 31 points by the start of February 2015.

Our View

There is not enough cargo for everyone to have ULCVs so future orders will be dictated by alliance needs and not those of individual lines. The window of opportunity for carriers to order 18-20,000 teu ships is closing and those that do not make the leap will struggle to compete on slot costs.

HEADLINES

- Do shipping markets want Biden or Trump for the win?

- All 18 crew safe after fire on Japanese-owned tanker off Singapore

- Singapore launching $44m co-investment initiative for maritime tech start-ups

- Cosco debuts Global Shipping Industry Chain Cooperation Initiative

- US warns of more shipping sanctions

- China continues seaport consolidation as Dalian offer goes unconditional