It’s All About Location for the ECB’s Reflation Campaign

In the 19-country patchwork that is the euro area, how well the European Central Bank’s quantitative easing program has gone since it started in March 2015 depends a lot on which country you’re looking at.

One of the four markers of a healthy inflation outlook that ECB President Mario Draghi set down in January is that price gains should be broad-based across the whole region.

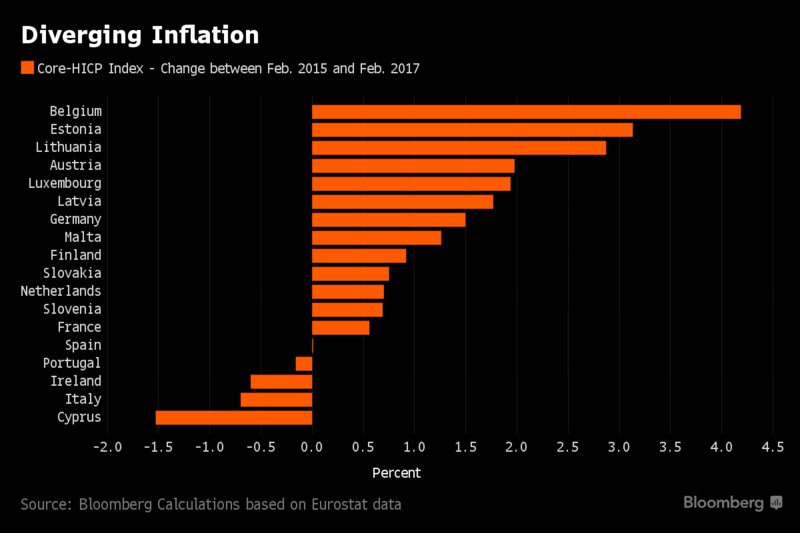

So while the ECB targets a euro-area average rate of inflation over the medium term of just under 2 percent, a look at the country breakdown can help show if that requirement is looking likely in the near term.

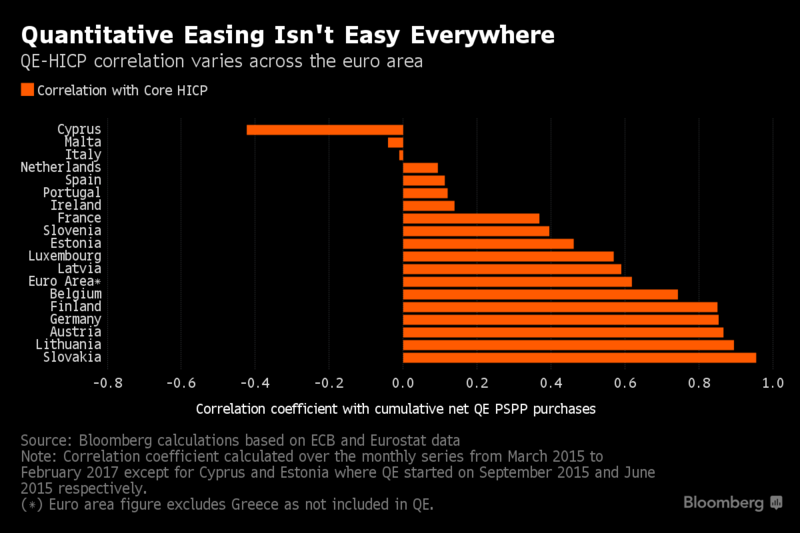

Bloomberg calculations show the impact of the 2.28 trillion-euro ($2.42 trillion) quantitative easing program, as reflected in the correlation between cumulative asset purchases and inflation adjusted for food, fuel, alcohol and tobacco.

The correlation coefficient is a measure that determines the degree to which two variables’ movements are associated. A positive correlation means the price index is rising in step with the stock of bonds owned by the ECB. A negative correlation means that as bond buying progressed, prices didn’t go up.

In Lithuania and Slovakia, small eastern European economies, the correlation is almost perfect. In Cyprus and Malta, where bond purchases either started late or have fallen short of the nominal target, the correlation is negative.

What’s more striking though is the difference between Germany and Italy. Europe’s largest economy displayed the fourth-highest positive correlation; the euro area’s third-largest economy is slightly negative.

For Italy alone, the total of net public-sector securities purchased under QE between March 2015 and March this year was 246 billion euros. Still, the Italian economy ended 2016 in deflation for the first time since 1959, as consumer prices posted a 0.1 percent decline on annual basis.

That underlines the mountain still to climb in the parts of the euro area with a lot of economic slack, high unemployment and structural reform still outstanding. It also gives weight to the ECB’s constant argument that no matter how much money it prints, it can’t substitute for upgrades to a country’s economic fabric.

“Although quantitative easing can be an effective way to help the central bank achieve its inflation objective in the medium term, it is not equally effective across countries and may actually prove ineffective in countries that are undergoing significant corporate-sector restructuring, as was the case of Italy,” said Raffaella Tenconi, a senior economist at Wood & Co. brokerage in London. Still, that is not “sufficient to prove that QE was counterproductive,” she added.

The ECB hasn’t published research on national inflation performance since QE, though an initial assessment from September last year argued that the asset-purchase program “contributes to stabilize the economy and push up the inflation rate.” As the chart shows, for some countries that’s more true than for others.

One of the main conclusions from the ECB’s own analyses of the impact of QE is against the counterfactual – how bad things would have been had the program not been there. The ECB’s estimate is that both economic growth and inflation over the past three years were 1.7 percentage point higher than would have been the case without QE.

Source: Bloomberg

HEADLINES

- Do shipping markets want Biden or Trump for the win?

- All 18 crew safe after fire on Japanese-owned tanker off Singapore

- Singapore launching $44m co-investment initiative for maritime tech start-ups

- Cosco debuts Global Shipping Industry Chain Cooperation Initiative

- US warns of more shipping sanctions

- China continues seaport consolidation as Dalian offer goes unconditional